South Korean Operations Director Michelle Randall at the Center for Quantum Nanoscience (QNS): A Research Facility with a Multi-Body Damper

At the Center for Quantum Nanoscience (QNS), nestled in the hilly campus of Seoul’s Ewha Womans University, director of operations, Michelle Randall, shows off the facilities. “This is where we isolate our scanning tunnelling microscopes (STM) from any vibrations,” she says, pointing to an 80-tonne concrete damper, a mechanism that reduces interfering movements to near zero. There is a desire by researchers at QnS to create a device that can control multiple qubits at once, something that was achieved last year with the creation of a device made from single atoms. Science 382 and 87. In collaboration with colleagues from Japan, Spain and the United States, QNS has done work that may have applications in quantum computing, sensing and communication.

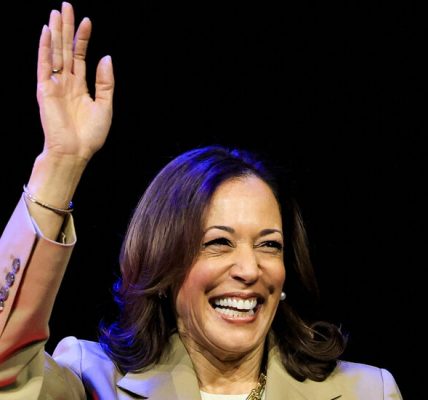

Randall says that QNS is helped by the diversity of teams that work in its labs. She says their composition is 50:50 South Korean and international and that they are an English-speaking workplace. She points to a room with four women, two South Koreans, one French, and one Iranian, which is a testament to the collaborative spirit.

The KoreanMinistry of Science and ICT’s (MSIT) wider R&D Innovation Plan includes an increase in the budget. The new Global R&D Strategy Map is a guide for tailored collaboration strategies with specific countries based on their strengths in certain technologies, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence and quantum science. The industry has strengths in 17 technologies which help achieve carbon neutrality and mitigate climate change. In addition, MSIT has amended laws to allow overseas research institutions to directly participate in state R&D projects and aims to develop Global R&D Flagship Projects in key areas that will receive prioritized allocation of government funds.

The term budget cut seems to means redistributing money to more applied projects and international research initiatives according to Computational Biologist, Martin Steinegger. Steinegger experienced a 15–25% reduction in existing grants, paid annually from the National Research Foundation of Korea, the country’s main funding agency. He had to use older hardware for research because of this. Steinegger says that he can apply to many new things even though he has less money.

The number of articles in the Nature Index that have been written by researchers from China and South Korea has increased by 222% over the last three years, compared with the US’s decrease. South Korean researchers say that their cooperation with China is more difficult in technology areas. The data from the National Police Agency of South Korea states that of 78 industrial technology leaks recorded over the last year, 51 involved people or places in China. There is now also more oversight of collaborations with China than with other major research partners. “Researchers occasionally receive requests from their institutions or the government asking who is collaborating with China, says Cha. They are aware of the fact that collaboration may be monitored.

According to Sung-Young Kim, who studies the role of government and is a political scientist at Macquarie University in Australia, Koreans do not think they are very good at R&D. For a country that has achieved remarkable economic development, a slowdown, especially compared with its competitors, is a source of anxiety for many South Koreans.

South Korea has a lot of interest in southeast Asia, which has potential to be used for joint innovation projects. She says that in Indonesia, there is no governmental institution that is in charge of the development of artificial intelligence.

Promoting high-risk, high-return research is a good strategy, but there are many social and cultural considerations to account for. The health-care system in South Korea is under pressure from the aging population and the worlds lowest birth rate. Previously, when science, technology and innovation were the government’s focus, the brightest students were drawn to disciplines such as engineering, says So Young Kim. Nowadays, they pursue medicine because of it being a secure well-paid and prestigious career with strong government support. In February, the government announced an increase to the national medical school intake quota from around 3,058 places — a number that has remained fairly consistent since 2006 — to 5,058 from 2025. So Young Kim thinks that by increasing the quota, it will hurt science and technology students. She says engineering programmes at the leading South Korean institution are hard to recruit from their own undergraduate programmes.

Religious and cultural differences pose problems. A student at Daegu’s Kyungpook National University who left Pakistan to pursue a PhD in computer science has sparked strong opposition from the local community for his mosque-reconstruction project next to his university. Razaq says he’s heard many stories from other Muslim students across South Korea who describe being taunted by their peers over food choices and who lack designated spaces for practices such as ablution before prayers.

South Korea has a culturally diverse business environment, but does not always treat foreigners as permanent residents: The case of Seoul Robotics

The brain pool programme, which gives PHD researchers access to 300 million won annually for three years, and Brain Pool Plus, which offers outstanding researchers with expertise in core technology fields up to 600 million won annually for up to ten years, can possibly be funded by the government. Support programmes are plans to help new arrivals settle in.

Seoul Robotics, a company that develops AI-powered software for autonomous driving and traffic management, has mandated an English-speaking work environment to attract international talent. Such a culture is unusual in South Korea; although many companies have English-speaking requirements, these are often not enforced, says Evan Thomas, business development manager at Seoul Robotics. He says that, compared to more traditional South Korean companies, the ability to communicate in English without a constant translation has been a significant advantage.

Cultural attitudes towards foreigners can also hinder long-term retention, says Thomas. “Many South Koreans view foreigners as temporary visitors rather than potential long-term residents, discouraging them from settling in,” he says. A survey by the Korea Institute of Public Administration, a government-sponsored research institute in Seoul, says less than half of the respondents accept foreign nationals as members of South Korean society.

Hong Bui was a student at QNS and after completing her PhD in technology, she was accepted into a post at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. Bui cites the limited permanent career opportunities that are available to international researchers in Seoul as one of her reasons for wanting to leave, despite having a positive experience in QNS’s internationally focused environment. She says that South Korean companies tend to value overseas experience more than domestic experience.

South Korea has an uphill battle ahead of it if it wants to regain its lead in technical innovation, but its historic ability to pivot in response to dramatic changes stand it in good stead, says Hemmert. “It’s a question of understanding what needs to be done, and then having the right leadership to implement the change.”

South Korea’s history has had a big impact on the national psyche, especially its development of innovative military technology, says Sung-Young Kim. He believes that technology is a source of national security. The nation pooled its limited resources to enable change after the government created strategic growth areas. Information and communications technology was one of the priority areas. Today, South Korea is a leader in fast broadband and next-generation mobile communications, but 50 years ago, there was an 18-month wait to connect a phone to the country’s antiquated network, says James Larson, who arrived as a peace corps volunteer in 1971 and now studies digital development at the State University of New York Korea, a campus of the US university located in Incheon.

The innovation review recommended that tailored programmes for funding science should be created. Many people we interviewed understood that they needed to support more high-risk, high-return research and that some people in positions of influence were starting to work on it. The level of change has not been fully appreciated. South Korea’s leading universities lack the freedom to make their own decisions. The government has designated some as ‘research universities’ — including Seoul National University (SNU) and KAIST — that receive more funds, “but instead of just leaving these well-resourced institutions alone to set strategies, there are still a lot of rules”, says Hemmert.

Regardless of the work being funded, a more fundamental issue that is stifling innovation in research is the short-term nature of funding. “Our funding programmes are usually very short, typically one or three years,” says So Young Kim. She adds that the mid-term performance milestone is set and a heavy emphasis is placed on measuring output in terms of top-tier journal publications. There is no way to continue your research if you are not successful in the current programme. The funding structure forces researchers to focus on quick wins.

He said that for cutting-edge research, you need to be more patient. He adds that research in Japan — where the same topic can be pursued for decades in multi-generational labs — offers an interesting point of reference. “Japanese scientists have picked up a good number of Nobel prizes, but South Korea has zero,” says Hemmert. Japanese scientists usually work on a particular scientific problem for decades when looking at their profiles.

Although the country’s research universities are often ranked highly in industry–academia metrics, there is room for improvement. “They understand the need to collaborate more, yet when it comes to implementation, it’s still a bit chequered.”

The government is considering other options for encouraging young people into science, such as expanding a programme that allows men to serve out their 18–21-month-long mandatory military service by continuing to work in their university labs. The bigger challenge is how we make studying science and technology enjoyable for people who are interested in it, says So Young Kim. She says that students and early career researchers often feel as though they are stuck doing manual labour in the lab, rather than being taught how to conduct research, which can be very unrewarding. It’s important to find intrinsic motivation for our students. Professors need to become role models, demonstrating that through this career we live a meaningful life,” says So Young Kim.