Feet of Clay Detector: Automatic Verification of Editorial Proposals and Retractions of Research Papers to Improve Publication Integrity

The publication and citation of literature is very important in academics. It can be hard to distinguish legitimate papers from dubious ones. There are many distortions because of this and the fact that the editorial, peer-review and publishing processes are highly reliant on trust.

Publishers should speed up their efforts to investigate, correct, and exonerate when it comes to investigations, corrections, and retractions. They should take firm responsibility for the articles they have published, and conduct regular checks so that retractions in their portfolios do not go unnoticed.

Publishers must update their practices and have more resources for both editorial and research-integrity teams.

A healthy scientific process includes the revision of flawed research papers. Not all retractions stem from misconduct — they can also occur when mistakes happen, such as when a research group realizes it can’t reproduce its results.

It is recommended by COPE that tools be used to assess publication integrity after publication. The literature on methods that assess publication integrity, including checklists applicable to a broad range of publications, is growing.

The guidelines from the committee on publication ethics suggest that they should be aware of retracted articles. The article PDF file is often edited to include a watermarked banner. But any copy downloaded before a retraction took place won’t include this crucial caveat.

All publishers should release the reference data of their catalogue to independent tools, such as the Feet of Clay Detector, to help them harvest data on the current status of articles.

The checks and balances are integrated into the integrity hub being developed by the association for the academic publishing industry that serves the editorial boards of subscribed publishers The software aims to flag any “suspicious” signals, such as tortured phrases, comments on PubPeer, or retracted references, to the editors.

Readers — especially reviewers — should be aware of red flags, such as tortured phrases and the possible machine-generation of texts by AI tools (including ChatGPT). Suspicious phrases that look like they might be machine-generated can be checked using tools such as the PPS Tortured Phrases Detector2.

The other is the Feet of Clay Detector, which serves to quickly spot those articles that cite annulled papers in their reference lists (see go.nature.com/3ysnj8f). I have added online comments to more than 1,700 articles to make sure that readers don’t forget the references.

Authors should check for any post-publication criticism or retraction when using a study, and certainly before including a reference in a manuscript draft.

Identifying nonsensical phrases in the scientific literature: a human-powered tool to monitor published papers for illegality and unauthorization

Two PubPeer extensions are very useful. One plug-in automatically flags any paper that has received comments on PubPeer, which can include corrections and retractions, when readers skim through journal websites. The other works in the reference manager Zotero to identify the same articles in a user’s digital library. Readers can check out the status of the article on the landing page if they click on the Crossmark button at the publisher’s website.

I devised a tool for the PPS to comb the literature for nonsensical ‘tortured phrases’ that are proliferating in the scientific literature (see ‘Lost in translation’). Each tortured phrase first needs to be spotted by a human reader, then added as a ‘fingerprint’ to the tool that regularly screens the literature using the 130 million scientific documents indexed by the data platform Dimensions. So far, 5,800 fingerprints have been checked. Humans are involved in a third step to check for false positives. The majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature, is a part of the Digital Science portfolio.

In February 2021, I launched the Problematic Paper Screener (PPS; see go.nature.com/473vsgb). This software originally flagged randomly generated text in published papers. It now tracks many issues to alert the scientific community to potential errors.

There are other ways to question a study after publication, such as on the PubPeer platform where a growing number of papers are being reported. Nearly all of the comments received on PubPeer were critical, as of 20 August. The authors of a paper that has been criticized aren’t obliged to respond. It is common for post-publication comments, including those from eminent researchers in the field, to raise potentially important issues that go unacknowledged by the authors and the publishing journal.

Journals are not very fast. The process requires journal staff to mediate a conversation between all parties — a discussion that authors of the criticized paper are typically reluctant to engage in and which sometimes involves extra data and post-publication reviewers. Most investigations can take months or years before the outcome is made public.

The conventional route to flag a paper for possible illegality is to call the editorial team of the journal in which it appeared. But it can be difficult to find out how to raise concerns, and who with. Some researchers might be unwilling or unable to enter the conversations because of the power dynamics at play.

Unscrupulous businesses known as paper mills have popped up that capitalize on this system. They produce manuscripts based on made-up, manipulated or plagiarised data, sell those fake manuscripts as well as authorship and citations, and engineer the peer-review process.

Performance metrics such as the number of papers published, citations acquired and peer-review reports submitted can help build a reputation and visibility for a researcher and they can even lead to invites to speak at conferences. This can give more weight to a promotion application, be important in attracting funding, and lead to more citations which can lead to a high-profile career. Institutions generally seem happy to host scientists who publish a lot, are highly cited and attract funding.

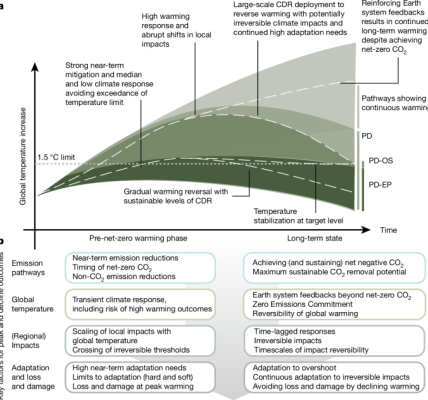

Over the past few decades, article retractions have increased, reaching a record high of almost 14,000 last year compared with fewer than 1,000 per year before 2009.

Assessing the false data in clinical-trial reports revealed by COPE: How should journals and publishers deal with ill-informed, unreliable research?

The assessment of clinical- trial reports sounded alarm bells in 2020. Out of 163 reports submitted to Anaesthesia, 45% were found to contain false data. This high proportion — which tallies with other estimates of the percentage of randomized controlled trials in medical journals that are unreliable — reveals a wealth of dubious publications in the public domain. The direction of future research, clinical guidelines and systematic reviews can be adversely affected by such papers.

Delays can be caused by recommended time frames for contacting institutions. If there is no response from the author or institution, the COPE recommends that journals keep calling the institution every 3 to 6 months, creating an endless loop. But institutions often struggle to provide timely, objective and expert assessments6, and focus heavily on perceived misconduct by their employees. They might be concerned mainly with protecting their reputations.

Publishers can pass the buck again as a result of this lack of clarity. For example, when the editorial board of the Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism recommended retracting 11 publications in 2020, the publisher, Springer Nature, refused to do so (go.nature.com/4fg9xes), on the basis that the university of the author in question had not investigated the matter, as was required under COPE guidelines. Nature is editorially independent from its publisher.

In our opinion, recommendations should include that journals routinely collect and verify key study information at the manuscript-submission stage. Details of ethical oversight and institutional governance — location, research infrastructure, funding and more — could be assessed by staff members before peer review, and statistical advisers could be employed to check raw data. These checks would reduce the number of papers needing such assessment after publication.

We think COPE should ensure that its guidance avoids accusative language such as ‘misconduct’ and ‘allegations’. Concentrating on the reliability of the study will lessen the need for journals and publishers to contact institutions before deciding on editorial action.

Critics might argue that this change of focus would make it less likely that misconduct would be exposed. Identifying integrity issues and fixing the literature can give us the reasons for compromised integrity.

And although COPE can apply sanctions to its members by revoking membership, to our knowledge it has never done so. The use of sanctions, and making that action public, would probably improve performance of journals and publishers.

Journals and publishers might argue that these recommendations would involve a lot of work. It is not worth doing if it seems daunting. The publishing industry is extremely profitable, and some of those profits should be invested in quality control.