Understanding AMR: What can we do about it? How to prevent infections in infants in the world – a case study of a Brazilian boy

More than 7 million die from infections each year. One-fifth of these are children under the age of five. According to a study published in The Lancet, at least half a million deaths could be avoided through strategies such as providing safe water and good Sanitation, isolating individuals with resistant bacteria, and increasing the frequency of hand washing in hospitals. Our study also indicates that the largest reduction in deaths would come from improving people’s access to antibiotics that are not available in many countries where most of the world’s bacterial-infection-related deaths occur.

There is a need for a global commitment to support research and data collection as well as investment in the basic interventions that will reduce it.

Thanks to biases in the available data, many people think, for instance, that resistance is ubiquitous. Physicians often give patients late-generation or last-resort antibiotics even though early-generation drugs could still work. This in itself might be worsening resistance.

For the babies at Shishu hospital, the most effective approach to saving lives is preventing infections from taking hold in the first place. Investing in parental nutrition during the critical stage of fetal development, ensuring that pregnant people get adequate care, and promoting delivery practices that minimize the risk of infants getting infections are all strategies that could substantially reduce AMR.

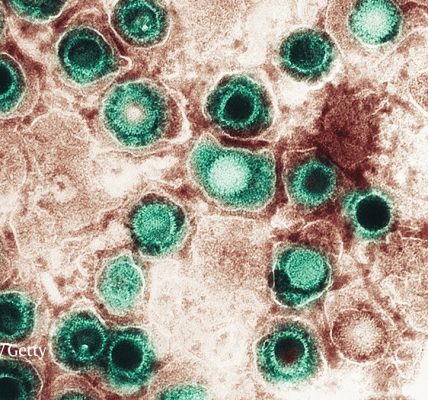

In five years time, a fifteen-year-old boy was brought into the hospital in So Paolo, Brazil, after developing an illness. He had cut his ankle while flying a kite. The boy developed a serious, systemic infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and died within 5 weeks after being admitted.

But as illustrated by the case I described, AMR does not occur only in hospital settings. And in Brazil, one of the biggest challenges is people’s failure to recognize AMR as a public-health problem. Most people who don’t work in hospitals lack the knowledge needed to understand what AMR is and how it could affect their health. There are many endemic diseases in the country, including Malaria, leishmaniasis and Chagas disease. And over the past 10 years, Brazil has experienced numerous epidemics caused by mosquito-borne viruses, including Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever, dengue and, most recently, Oropouche fever. AMR is harder for people to identify a cause for because it gets more attention.

Modest investment could also improve infection prevention and control practices at health-care facilities — such as promoting handwashing or the isolation of people infected with antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. In 2020, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention released updated guidelines on infection control and prevention. According to a study published in the Lancet series, guidelines that are followed can prevent 300,000 deaths worldwide from infections that are resistant to antibiotics.

Transforming this plan into a successful programme, similar to the country’s vaccination, HIV and hepatitis schemes, will require more political buy-in and a lot more investment in efforts to raise public awareness. It will require the integration of priorities for both humans and animals. Government officials, clinicians, and scientists don’t need access to advanced technologies to make a difference. More parents and caregivers need to be vaccined and more people should be avoiding the use of antimicrobials, so that the nation’s basic Sanitation programme can be expanded.

One-quarter of Nigeria’s population defecates outside, such as in fields, gutters and forests, instead of using a toilet, some or all of the time. There was data from a report in the year 2024. I was involved in show that most city residents rely on household water from wells or boreholes that is contaminated by faeces. This is the case in Ibadan, where I live. Agents of disease — including typhoid, diarrhoea and cholera — can spread easily, as can non-harmful (commensal) organisms harbouring resistance genes that can be transmitted to pathogenic bacteria. Escherichia coli is a type of microorganism found in the intestine. Providing people with safe water and better sanitation could reduce the impact of both enteric infections (stomach or intestinal illnesses caused by microbes, such as viruses, bacteria and parasites) and AMR simultaneously, yielding an estimated return of US$5 or more for every $1 spent4.

I am constantly worrying about whether my mother, who has a recurrent infection of the urinary tract (which is resistant to most antibiotics), will be able to keep accessing the health-care services and antibiotics she needs. She lives in Beirut, Lebanon, and I am always reminding her to keep her passport and antibiotics to hand in case she has to flee in the face of a military attack.

Global Action to Address AMR at the UN High-level Meeting on Human Rights and Children’s Health (Call 18-2024), Washington DC, April 27 – 30 September 2017

In 2017, Nigeria launched an AMR surveillance system. Once this system covers a greater geographical area and more comprehensive data are collected — from people, animals and the environment — investigators will be able to quantify the impacts of each of these tools and support the prioritization of interventions for national deployment.

This is the second time that AMR has been featured at a high-level UN meeting. The first one, in 2016, highlighted the importance of the problem, which is associated with nearly five million deaths each year worldwide. The pace of change has been slow even though there have been some improvements in the past eight years. I am presenting at the upcoming meeting, and I hope to convince attendees that the next eight years could look very different.

Malaria and most bacterial infections do not last as long as do tuberculosis or AIDS, from which people tend to die months or years after infection. A child with an infection who develops a fever in the morning can be dead the next day if they don’t receive the right antibiotics. But in low- and middle-income countries, those are unavailable in many public-sector clinics. Parents and other carers must frequently turn to their local pharmacies for help. Billions of people are using those drugs because it is harder to set up systems that limit the entry of poor-quality or fake drugs in the public sector.

International funders such as the Global Fund have to step up. People with HIV are more likely to get infections than the general population. Providing people with access to effective diagnostics and antibiotics targeting bacterial infections more broadly would be a natural extension of the Global Fund’s existing mandate.

Furthermore, prevention strategies — especially the provision of vaccines, safe water and good sanitation — need to be supported by organizations such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, as well as through bilateral donors, including the United States Agency for International Development in Washington DC. They need to be prioritized in the budgets of low and middle income countries.

With investment from global funders, specific targets and accountability through an independent panel, there is a chance of this year’s discussion at the General Assembly bringing about global action to tackle AMR.