The Discovery of Alzheimer’s Disease: a Case Study of the Christchurch Mutation and its Genome-Induced Therapeutic Effects on Microglia

In 1982, neurologist Francisco Lopera and his colleagues at the University of Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia, began studying a family for whom Alzheimer’s disease was a fact of life. Members of this family would invariably develop mild cognitive impairment at around 45 years of age. This would progress to dementia by the age of 50 and end before their 60th birthday if tangles of Alzheimer’s are not destroyed before that time.

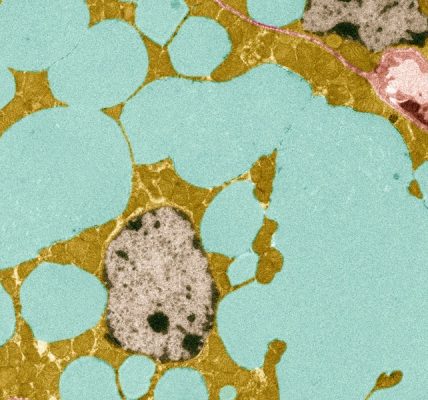

The group of Huang and his associates are looking at developing therapies for the brain that can be done with smaller, easier- to-pilot Molecules and exploring gene therapies. Holtzman is pursuing drugs inspired by the Christchurch mutation, with a focus on cells in the brain known as microglia.

The team, led by Yadong Huang, a neuroscientist at the San Francisco, California, made a study on the possible protection from Alzheimer’s through a mixture of model systems. It found that engineering the mutation into the APOE4 gene reduces the accumulation of tau, as well as the neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration that would otherwise be expected5. It is striking that a large amount of protection can be achieved by the Christchurch mutation.

Genetic testing showed that PSEN1 was not her only mutated gene. A variation of the gene APOE was carried by her. One form of this gene, APOE4, is a major risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The lower risk versions and the no effect versions are the other versions.

But in every family, there is someone who goes against the grain. This is the case of a person who has a story that challenges the understanding of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

It is difficult to understand how hard it is for a person to find out they have Alzheimer’s disease until you experience it yourself. Seven million new cases of Alzheimers are diagnosed every year and too many will come to know about it.

The first therapy to be used for Alzheimer’s targets the amyloid- in the brain. The deposits are cleared that slows cognitive decline. The task now is to achieve stronger effects by building on anti-amyloid therapy or combining it with drugs that target other aspects of the disease.

Blood tests that can differentiate Alzheimer’s from other forms of dementia have been developed over the past five years. Although these tests look like a great way to aid physicians and researchers, there are concerns over their use by consumers.

The Outlook: Including Contributions of Eli Lilly & Company to Photon Production at the Tevatron Collider at the CERN SPS

Thanks to Eli Lilly & Company, we are able to acknowledge their financial support of the Outlook. As always, Nature retains sole responsibility for all editorial content.