Science is not well represented in diplomatic politics or peace-building: A comment on recent UN climate talks in Busan, Korea, and in Cali, Colombia

The international community is also sharply divided on the scope of an agreement that is being negotiated to end plastics pollution. The latest talks in Busan, South Korea, have been extended into 2025. Talks on a treaty to fight the spread of disease were put off until next year. African nations are at odds with Europe and the United States over a request that low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) should have preferential access to pandemic-related products that are developed using their data.

It is worth reflecting on why research is struggling to have an impact. When the present system of science advice in UN meetings was originally established, the United States and European countries were the world’s largest economies. Their delegates dominated proceedings and made an outsize presence during talks. Many of the research that underpinned UN environmental agreements came from these nations, as did the scientists observing the talks and the influential media outlets covering them.

The UN COP16 biodiversity meeting in Cali, Colombia, also ended without the funding boost needed to restore and protect nature. Countries pledged $163 million, which is orders of magnitude short of the $200 billion a year needed to reach the goal of protecting 30% of the world’s land and seas by 2030. Delegates did agree that large companies should pay if they made a profit using genetic information from nature, but payments will be voluntary.

Even though groups of scientists in several countries have proposed ways to end plastic pollution, they are struggling to make their voices heard at the talks on a plastics treaty. The UN needs to organize a system for researchers to advise during the discussions.

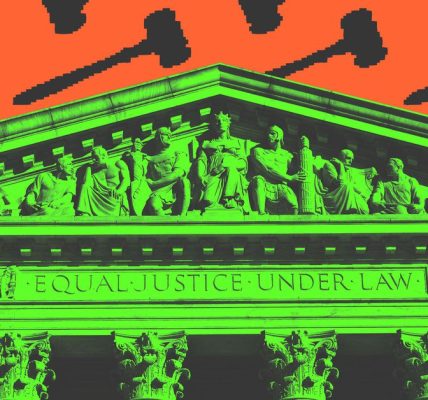

This is important work not just for the knowledge and skills it will generate, but also because it will give scientists visibility in fields in which they can lack influence. Science is often not well represented in diplomacy or peace-building, a point also made in a Communications Engineering comment article published last month (M. M. López et al. Commun. Eng. 3, 159; 2024). The authors of the article state that peace-building efforts are led by people with previous experience in politics, diplomacy, and humanitarian relief. Those with a background in science, engineering, and technology should be involved in strategic planning. Peace itself is foundational to the SDGs, not least SDG 16: peace, justice and strong institutions. “When regions are destabilized, research is often interrupted, resources diverted, partnerships falter and knowledge exchange and innovation uptake come to a halt,” say Clarke-Habibi and Korsten.

Wars in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan have made the past year one of the deadliest in recent times, according to the latest Armed Conflict Survey (see go.nature.com/3z565x), produced by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), based in London. Worldwide, nearly 200,000 people were killed between 1 July 2023 and 30 June 2024, a 37% rise from the previous 12-month period. Mark Rutte, the former Netherlands prime minister, now head of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), said last week that NATO must prepare for a “wartime mindset”, and urged member states to allocate more money to military budgets. The world’s military spending has increased in nine consecutive years, reaching an all-time high of nearly US$ 2.5 trillion in the 12 months ending in June. Military spending increased in Africa by a fifth. But are wars more likely? Why can’t peace be more of a priority? These questions need to be asked, and they make a new initiative called Science 4 Peace Africa all the more timely.

The president of the African Academy of Sciences ( AAS) and a peace building expert from the United Nations Institute for Training and Research were in Nigeria last week.

The fall of the Assad regime: a positive change in an era of violence, conflict, and violence in the region of Aleppo

The fall of the Assad regime was a rare and positive development in what has mostly been another devastating year of violence and conflict.