How Post-baccalaureate Positions Can Help Students in Their Research Careers: A Case Study in Transiting Exoplanets

Robbins and Brande had to chart their own courses in a way that is not uncommon in fields such as physics and astronomy. A specific search can sometimes return a few opportunities, although the American Astronomical Society does not include post-bacs as a category. MacGregor says this is why she turned to social media for help after she was approached by a few students. “I find that post-bacs are very poorly advertised and not discussed very much. She thinks graduate admissions becoming kind of a nightmare is tied to that. Her own astronomy department at Johns Hopkins received more than 400 applications for 10 PhD student slots for the 2024–25 academic year.

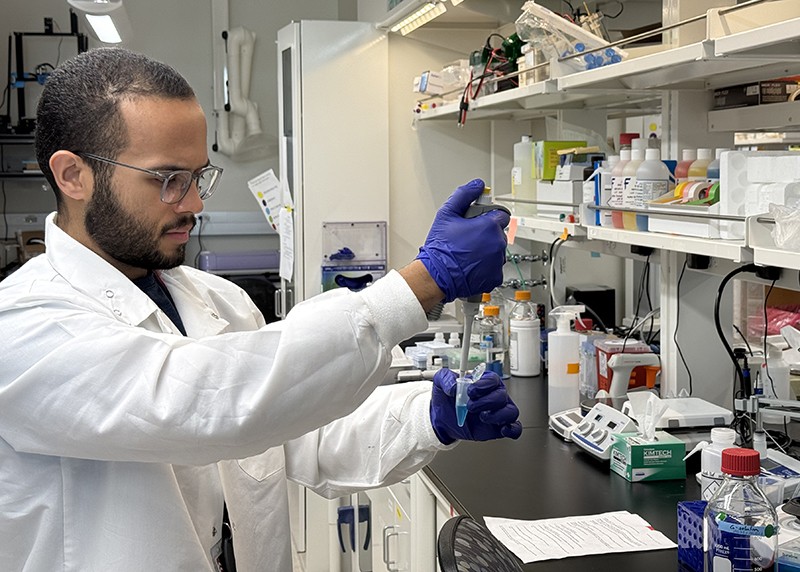

The post was a plea to connect recent university graduates with principal investigators (PIs) who could provide research experience in their labs for a year or more. These post-baccalaureate positions, or post-bacs for short, can be a stepping stone to graduate school for a master’s or PhD in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). STEM graduates who did not get enough lab- or field-based research experience at university might consider a post-bac position to make their applications to PhD programmes more competitive — even though it adds a few more rungs to an already long career ladder.

A post-bac degree can be used to gain research experience and scientific skills before graduate school. For some people, a post-bac provides time to work out what areas of research they’re interested in. It seems that US post-bacs are a phenomenon.

For others, it’s just that. Gwen Robbins says she was going to graduate from college straight after her degree in astronomy. That didn’t work. The university connected her with the scientists at the APL when she didn’t have any research projects on her CV. Robbins says that they offered her a position as an intern for a year to assist in various projects related to the NASA missions.

Over two and a half years, Brande developed a keen interest in the burgeoning field of transiting exoplanets — the study of planets beyond the Solar System that are caught passing in front of their host star. The experience provided him with clarity on his research goals, as well as new computational skills, and practice for his academic writing. He started the astronomy PhD programme at the University of Kansas in 2020.

Source: Do you need extra training before graduate school? Consider a post-baccalaureate position

The Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program: Building a Scientific Identity for Post-Baccuracy Students in the Biomedical Sciences

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Robbins got hands on laboratory research experience that she couldn’t get from her university. Robbins is still looking for a graduate position three years later.

It isn’t uncommon for graduates in the United States to try to improve their practical research experience between university and graduate school. Although it is common for students in some countries, especially those in Europe, to seek a master’s degree that fulfils these goals before starting a PhD, the proportion of practical research to graduate coursework varies in these courses. Students can go from an applied-sciences bachelor’s degree to graduate study in more basic sciences in India. To ease that switch, they often spend a year in a ‘project student’ position — a position similar to a post-bac.

Many post-bac experiences are not formally structured or advertised. Abhang worked six months for no pay and Brande and Robbins received stipends that were enough to cover living costs but not health insurance. Some students, such as Brande and Abhang, say they had good mentors who provided clear career guidance.

The field of biomedical sciences has one of the oldest continuously running post-bac programmes. The Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program (PREP), which is funded by the US National Institutes of Health, started in 2000 and is active at 58 US institutions. In the past decade, between 73– 2% of PREP graduates have successfully transitioned into a PhD programme, delivering on their goal to develop a diverse pool of early-career researchers. In order to make up for cost-of-living differences, institutions may supplement the base salary of PREP scholars that is usually US$40,000 per year. The programme in PREP is more structured and has more opportunities for development than in an independent lab.

“Building a science identity is really important to help post-bac trainees visualize themselves as a graduate student and as a scientist,” says Donita Robinson, a neuroscientist and the PI of the PREP programme grant at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill.

Robinson outlines a typical PREP year at UNC starting in June with a boot camp in which students are taught how to interpret and discuss scientific papers, alongside meetings with faculty members to choose a lab for the next 11 months. In the lab, students take a graduate course to strengthen core concepts, improve competency or offset low undergraduate marks. Poor grades can be attributed to life circumstances, rather than being related to an individual’s aptitude. Students are encouraged to present their research at a science conference in December or January, so they can hone their presentation skills and get access to networking opportunities. Around the same time, the PREP programme supports students in their graduate-school applications, such as providing them with help to prepare for the Graduate Record Examination (a standardized test required for graduate admissions in many universities in the United States), writing research statements, selecting universities and labs and sourcing recommendation letters.

Why scientists should learn how to build their networks for careers: The case of a large research network in the UK and why scientists are not satisfied with their research qualifications

The large online platforms that connect researchers to potential employers need to become less robotic. Often, candidates will submit a job application in response to an advertisement and hear nothing back beyond an automated acknowledgement. Many recruiters state that they will not provide feedback to unsuccessful applicants. That is understandable for positions that may attract a lot of applicants. It’s demoralizing to jobseekers because it makes them think that an unambitious employer wouldn’t want to hire them.

Nature interviewed some recruiters who wanted to hire in their professional networks instead of relying on the big online platforms. This is to stop cut-and-paste applications or those that use artificial-intelligence tools. This shows the continued importance of networks for career development, and means that those entering the job market should receive training in how to build networks.

The path forward requires jobseekers and recruiters to understand each other better. Candidates would benefit from learning why recruiters are dissatisfied with the calibre of applicants. The institutions have a responsibility to see themselves as architects of scientific careers. This means acknowledging that professional preparation isn’t a distraction from research excellence — it is an essential component of it.

Meanwhile, employers responding to Nature’s survey report that candidates often lack creative thinking, problem-solving and communication skills and qualities such as persistence, passion and tenacity. There is no structured training for jobseekers on how they can learn and show evidence for these characteristics.

Shifting generational priorities also play a part. The most current early-career scientists are born between the early 1980s and mid-1990s. They often bring with them digitally savvy and a desire to see how their work affects society. They also tend to value work–life balance and career flexibility, which might not always square with the priorities of the scientists interviewing them for jobs.

The perception that someone with a science qualification is fully qualified for research work is the main cause of the mismatch. A PhD is usually an equivalent of an entry-level qualification, with the holder requiring further advice, guidance, mentoring and experience before they can work on their own.