What science photos do that AI-generated images can’t: How governments are destroying the US government’s climate commitments to global warming?

People in low and middle income countries are more likely to be affected by breast cancer. Plus, what science photography does that AI-generated images can’t.

Low- and middle-income people are more likely to die of breast cancer because they don’t have the same screening and treatment options. For example, people aged under 50 in low-income countries are four times more likely to die from breast cancer than those in high-income countries, on the basis of the most-recent available data, from 2022. Because of increasing life expectancy and changing prevalence of risk factors — such as obesity, drinking alcohol, and less breastfeeding — breast cancer cases and deaths are predicted to rise over the next 25 years, with the greatest increase in LMICs.

Through actions such as firing of US federal scientists en masse, blocking clean-energy incentives and abandoning international climate commitments, the administration of US president Donald Trump is hobbling the country’s efforts to reduce its contribution to global warming. As courts start to assess the legality of some of Trump’s policies, the uncertainty is hampering climate- and energy-related programmes and businesses. Daniel Cohan says that he hadn’t anticipated that tearing everything down without a plan would be vicious.

Meanwhile, a coalition of nonprofit groups, archivists and researchers are working to ensure that the federal environmental data they rely on remains available to the public. Alejandro Paz and Eric Nost are members of the Public Environmental Data Partners network and have written about how to find and save US government data.

Source: Daily briefing: What science photos do that AI-generated images can’t

What do you know about your reef? How can you use genAI to promote climate science communication? A case study of Sholei Croom

Do you know anything about your reef from your loss or theft? Scouts and seafarers will know that these are similar-looking knots, and the reef is strongest. Sholei Croom, a brain scientist, says the grief knot is so weak that it would fall apart if you sneeze on it. But people aren’t that good at guessing which knot is stronger just by looking at them — even when they showed a good understanding of the underlying structure. Researchers say that the blind spot in physical reasoning sheds light on how our brains perceive the world.

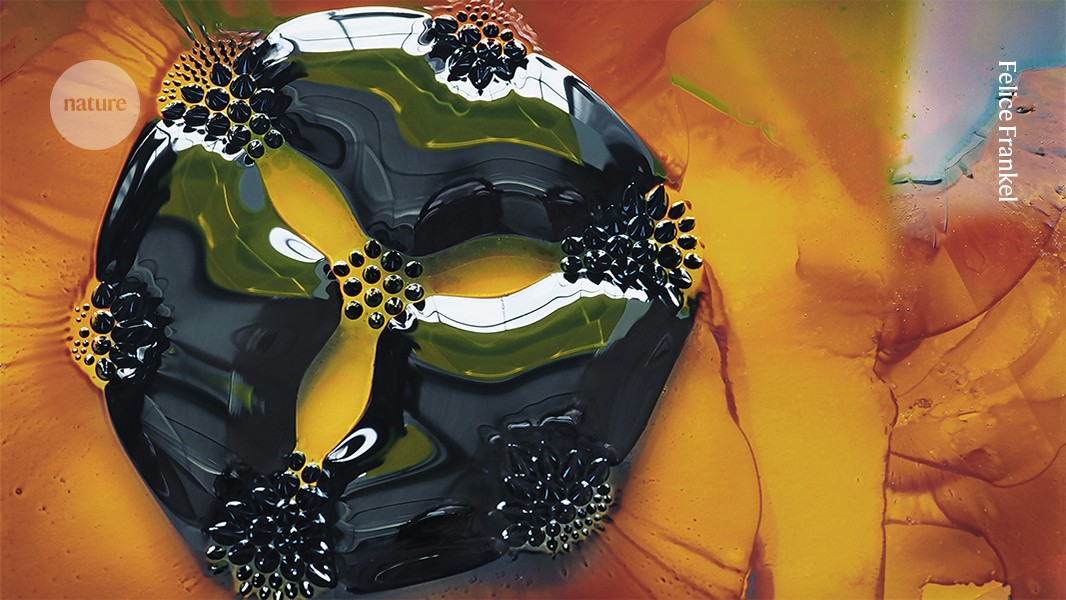

But now, with the wide availability of generative artificial intelligence (genAI) tools, lots of questions must be asked. If a scientist only needs a few words and a few commands, they can create a visual of their research and then use that image as a record of their work. Will researchers, journals and readers be able to spot when an image is created for a purpose other than documenting the work? From a personal point of view, is there a place for a science photographer like myself to advance the communication of research? Experiments with artificial intelligence image generators have revealed what I know.

Communication is used to push climate action, but is overlooked by researchers. It is possible that climate science can be made more accessible to the public by engaging storytellers who celebrate the joy of nature. These stories must be accessible in as many languages as possible, and elevate the knowledge of Indigenous communities. Nagendra wrote about sharing the stage with others that are affected by climate change to understand how it feels.

Do I understand everything? A Photograph of Moungi Bawendi and the Three Views in DALL-E Using Fluorescent Nanocrystals

Researchers have been eavesdropping on unusually close-knit families of carrion crows (corvus corone corone) in Spain, collecting data on hundreds of thousands of different vocalizations. Small microphones recorded a variety of soft calls, far quieter than the familiar ‘caws’. The sounds were analysed and made into a group by the team. The researchers will try to better understand how crows co-exist with humans.

In their book, Discarded, Sarah Gabbott and Jan Zalasiewicz write that synthetic clothing will leave no trace in the fossil record, as it degrades over the course of thousands of years. 7 min read by The Guardian.

One of the privileges of being on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge is seeing glimpses of the future, from advances in quantum computing and energy sustainability and production, to designing new antibiotics. Do I understand everything? No, but I am able to wrap my head around much of it when I am asked to create an image to document the research.

To start we need to remember the differences between a photograph and a Genai visual, created with a diffuse model, which is a complex computation that makes something that seems real but might never have existed.

A chemist at MIT asked me to take a picture of his quantum dots. When excited with ultraviolet light, these crystals fluoresce at different wavelengths depending on their size. Bawendi, who later shared a Nobel prize for this work, did not like the first image (see ‘Three views’), in which I had placed the vials flat on the lab bench, taking a top-down photograph. You can tell that was how I had placed them, because you can see the air bubbles in the tubes. I thought it made the image more interesting.

The Journal of Physical Chemistry B had a cover with the second iteration. That photograph provides a straightforward record of the research and highlights the importance of collaborating with the scientist — an essential part of my process.

To create a similar image in DALL-E, I used the prompt, “create a photo of Moungi Bawendi’s nanocrystals in vials against a black background, fluorescing at different wavelengths, depending on their size, when excited with UV light”.

More troubling is the fact that, in each vial, there are dots with different colours, implying that the samples contain a mix of materials that fluoresce at a range of wavelengths — this is inaccurate. Some of the dots are on the table. Was it an aesthetic decision made by the model? The resulting visual is very interesting.

Taking the point further, all of the amazing images we see of the Universe are now digitally enhanced, giving us yet more representations of reality. Seen through this lens, it is clear that humans have been, in effect, artificially generating images for years, without necessarily labelling them as such. However, there is a crucial difference between enhancing a photograph with software to depict reality and creating a reality from trained data sets.

The intent is to describe and clarify the work with an illustration. GenAI visuals will probably excel in that task. But for a documentary photograph, the intent is to bring us as close to reality as we can. The ethics of both are already being manipulated by artificial generation, and so the importance of defining them and discussing them is paramount.

Publishers now have software in place to identify various manipulations in images that already exist (see Nature 626, 697–698; 2024), but, frankly, AI programs will eventually be able to circumvent these fail-safes. Efforts are being made to find a way to trace the provenance of a photograph or document any manipulation of it. For example, the forensic photography community, through the global Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, provides technical information to camera manufacturers regarding the ability to trace the provenance of a photograph by keeping a record in the camera of any manipulation. Not all manufacturers are on board.

An important issue has been raised by two articles about privacy and copyright violations when using diffusion models. You can pre-print at arXiv at gnqmsb. In a closed system it is possible for credit to be feasible if training data are known and documented. For example, Springer Nature, which publishes Nature (Nature is independent of its publisher), has recently included an exception into its policy for Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold program to cover this sort of use (for models trained on a specific set of scientific data). The AlphaFold tool doesn’t create images by using Genai tools, but by generating structural models that are turned into images by people.

Efforts are made to address privacy issues. Adobe explains in its manual that Content Credentials can be used by creators, to get proper recognition and promote transparency in the content creation process.

In one instance, I recall that an engineer altered a photograph I had made of their research and wanted to publish it along with the submitted article. The researcher didn’t consider changing the image to be similar to changing their data, as they hadn’t been taught basic ethics of image manipulation and visual communication.