The Green Labs Program: Challenges and Challenges to Promote Collaboration and Sustainability in the Laboratory Ecosystem – An Introduction and Report on Results and Issues

Lab Scientists express a clear will to change when I meet them. Since researchers face a high amount of pressure to publish their results quickly and with the highest possible scientific impact, it can be hard to prioritize green actions. This is why I greatly value green lab-certification programmes and challenges; they form powerful tools to motivate action.

The Green Lab’s certification programme requires labs to meet certain standards and benchmarks for the use of energy, water and supplies. Those wanting to participate in the process have to apply and pay a fee of between $500 and $4,000. Around 1,200 labs have been certified so far in 47 countries. Not all will qualify for certification, but successful applicants are awarded a wall plaque. Certification lasts for two years; if a lab wants to remain certified after that, it has to go through the process again.

Environmentally Responsible Science: An Action Plan to Reduce Redundancy in the Carbon Neutral Laboratory of the University of Nottingham, UK, Inspired by Environment, Health, and Moral Responsibility

I think that academic leaders in particular — with their decision-making power and role-model function — have a moral obligation to act. A 2023 study4 shows that when leaders in an organization demonstrate responsible and environmentally conscious behaviour, employees are encouraged to do so, too.

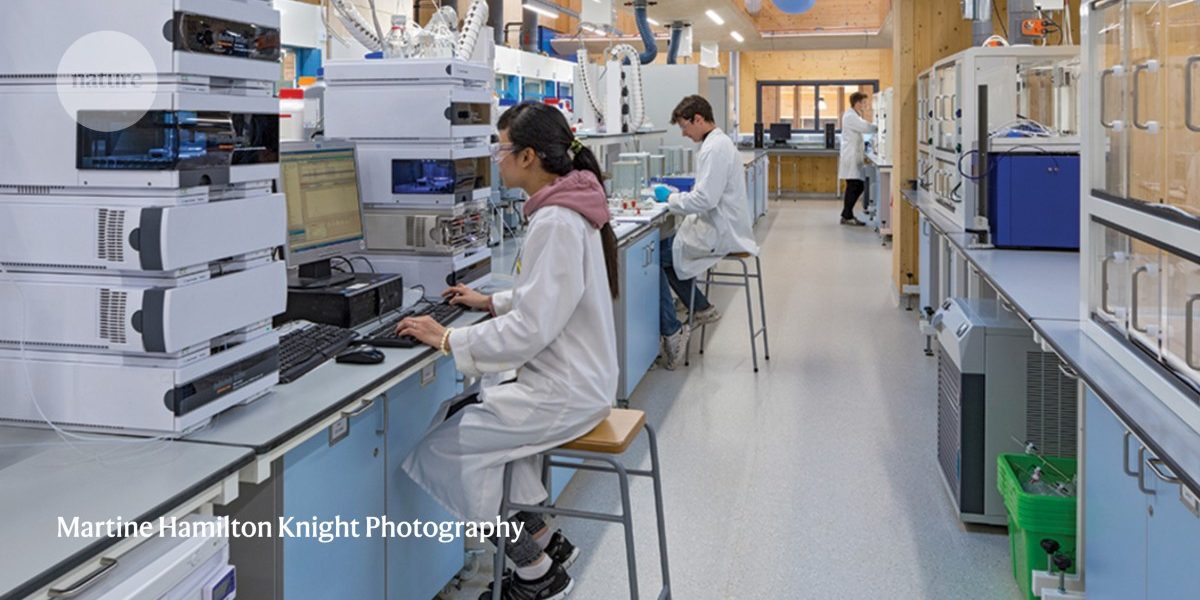

Despite some setbacks, sustainability is also leading to savings for the Carbon Neutral Laboratory, a one-of-a-kind facility at the University of Nottingham, UK. The lab cost $20.8 million to open and most of its funding was provided by a multinational pharmaceutical company. The building partly powered by solar panels and a heat system is designed to consume less power than a lab of the same size. Peter Licence is the director of the lab and he says that they are paying back carbon used for construction by not buying electricity from the grid. “The whole concept is an experiment.”

Inspired by many other individuals who share values such as climate justice, care and collective action, I turned my fear about our planet into concrete actions and began to experience feelings of empowerment and hope.

We set up our foundation during the early stage of what feels like a wave of grass-roots initiatives in science and health care. More than 100 green initiatives for health transition have arisen in the Netherlands over the past 3 years under the umbrella of the Dutch Green Health Alliance. The fear of an environmental catastrophe is at a high, with many surveys showing the distress that negative environmental news is causing.

Durgan says that scientists could make a difference by rethinking their approach to planning and executing experiments. It is possible to cut down on redundant tests and experiments if they planned more carefully, which would save money and time. Being as critical as you can be about the experiment you choose to do, and the one at the front end, is a good way to do your science anyway.

Before scientists make any changes to their protocols, they should be confident that their results won’t be affected. Freese says that you should use 20 litres of solvent and 20 pipette tips for your research. If you conduct more experiments it will mean that your results are more significant.

Chemicals that have been part of a standard protocol for decades are encouraged to be used less at the Carbon Neutral Laboratory. Licence says that if he has to use dichloromethane, he will look for an alternative.

The Carbon Neutral Laboratory found savings through collaboration, he says. “We share a lot of things like fume hoods and spectrometers,” says Licence. Sharing can save space and energy, while also promoting conversation and collaboration. The entire building is designed to make you think differently. Students and academics share ideas, work together and often translate knowledge in a much more rapid and much less siloed way than we would have in a traditional old-school chemistry department.”

Still, it will take some time for the lab to live up to its name. The goal was to have net carbon neutral in 25 years, enough time to allow energy savings to offset the energy needed for its construction. There are problems with some of the mechanical, electrical and combined heat and power units that run on bio-energy, and we are slightly behind target at the moment. “I’m fairly confident that we will achieve carbon neutrality by the 25-year time frame. But where we sit right now, I would say that we’re probably three, four or five years behind that payback schedule.”

A 2024 report in the journal RSC Sustainability laid out some eye-opening statistics: at a typical university, research laboratories account for at least 60% of the energy and water use1. Researchers have a work carbon footprint that is 7–25 times greater than the per-person climate maintenance guideline set out in the Paris agreement, according to their field of study.

Push a few buttons can be as simple as taking a step. Durgan explains that the Babraham’s labs turned the temperature of their 40 ultra-cold freezers up, from −80 °C to −70 °C . Some researchers warned that, if the freezers ever malfunctioned, the samples would spoil faster without that extra 10 °C cushion. To ease those concerns, Durgan spoke to Martin Howes, then the sustainable-labs coordinator at the University of Cambridge, UK, who reported that scientists there had made the adjustment without any issues. She was reassured by the researchers who reported their experiences with 70 C freezers to My Green Lab. At the Babraham, the move reduced energy consumption by nearly 20% without affecting the frozen samples.

Fume hoods are also prime targets in energy-conservation efforts. As outlined in the RSC Sustainability report, a typical fume hood uses 3.5 times more energy than an average household does each year1. The cost to run a hood in a lab is estimated to be US$4,500 annually by Harvard University. A simple sliding window close at the front of the hood can cut the air flow rate by two-thirds, with similar reductions in energy expenditure. Energy costs were reduced by $200,000 each year because of Harvard’s initiative to close fume hoods.

Other steps are not always clear-cut. “You might think about trading some plastic items for reusable glassware,” she says. “But that’s going to use water, and it’s going to require energy to sterilize the glass.”

Third-party verification of lab supplies for environmental conservation and clean manufacturing processes – A case study in Groningen, N Ireland with the Marine Institute of Ireland

Durgan adds that any cutbacks in the name of sustainability could lead to more waste if the research results aren’t reliable. The international research community is going to waste a lot of time and money if we don’t make sure our data is robust and reliable, she says.

Scientists can’t just look at manufacturers’ labels to determine which products deliver efficiency without compromising research results In a practice known as greenwashing, firms can attach claims of sustainability to truly wasteful products. Companies are using their own standards. If you don’t have third-party verification, you need to be smart to know which standards are legit and which aren’t.

In order to improve clarity, My Green Lab has set up a database of independently generated environmental- impact scores for more than 1,200 lab supplies. The full life of a product, including its manufacturing impact and use of energy and water, packaging and ultimate disposal are taken into account in the scores presented on the label.

Durgan says funding agencies are the only entities that can bring change. Funding is going to depend on people being more sustainable because they are more motivated from an environmental point of view.

In a statement to Nature, the NIH Office of Extramural Research said it doesn’t require lab certification, but does “consider the scientific environment during peer review and monitor compliance with all requirements post-award through our grants oversight procedures”.

Cost savings can also serve as an incentive. The University of Groningen had 46 laboratories that received LEAF certification that were able to save over $440,000 a year by adopting energy-saving measures.

Lab results have been even more impressive. Jane Kilcoyne, a research chemist at the Marine Institute in Dublin, Ireland, achieved annual savings of $16,000 by turning up the temperature of his freezers, closing his fume hoods, and ordering only needed solutions and reagents.